Richard Butler | Exclusive Report by Sachin Tiwari of The Diplomat NEWS | JAN 4th, 2023

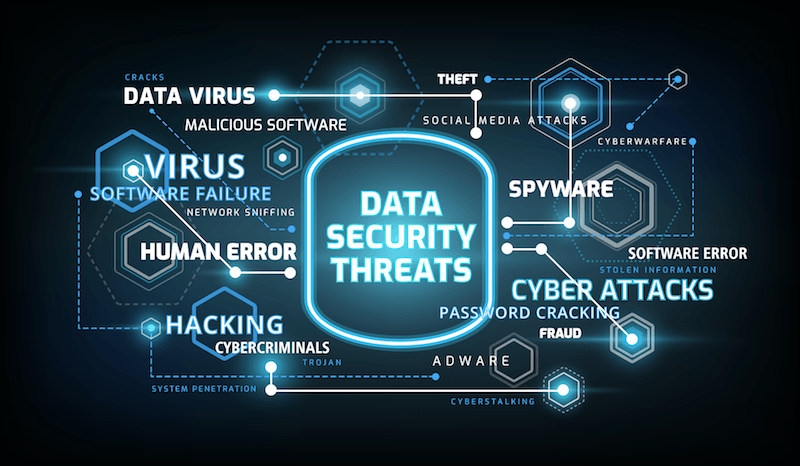

From the attack on AIIMS in India to the cyberattack that crippled Vanuatu, the national security threat of ransomware is clear.

The 2021 report by cybersecurity firm Sophos found that 78 percent of Indian firms were targeted by ransomware attacks, signifying the rising level of such crimes. Similar trends are visible across the Indo-Pacific, with countries in the region among the most targeted by ransomware attacks in the previous year. However, these incidents are not limited to private industry but cut across to sensitive targets termed as critical to national interests.

The recent ransomware attack on AIIMS, one of the largest public health institutions in India, highlighted the dangers cyberattacks can pose to human life. Attackers targeted AIIMS servers with malware that made the servers dysfunctional. Various services were affected, from patient registration to emergency services, affecting patients and curtailing hospital operations for several days. And that was in addition to the leak of personal data in large numbers, including information on key individual.

2022 trends suggest that the healthcare industry is the second-most targeted (after the manufacturing sector) for ransomware attacks. The problem is global in nature. Cyberattacks targeting small island nation Vanuatu in the Pacific in November 2022 had a major impact on government networks and crippled services. Another major ransomware attack on the Colonial pipeline in 2020 led to a massive disruption in fuel supplies in the eastern United States.

Ransomware not only brings economic loss, but represents the complexity of the cyber domain, where attacks can be made for economic, political, or military gains. Ransomware has thus emerged as a major national security threat.

Cyberspace has developed into part of normal statecraft. Nations around the world are actively engaging in cyberspace, with the presence of both state actors and sophisticated non-state groups. These include covert cyberattacks in the form of intelligence operations as well as disruption and exploitation for economic gains. The Snowden leaks revealed the intelligence operations by the United States, while China conducts large-scale cyber espionage for economic interests as well as intelligence gains. The 2015 agreement between the United States and China differentiated between espionage for national security purposes and commercial espionage.

In the case of ransomware, commercial gains can be combined with more strategic goals connected to political and military goals. The series of ransomware attacks in 2017, including WannaCry, targeted computer systems across several countries, including the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. As opposed to covert intelligence operations, ransomware has overt effects – it targets the victim both psychologically as well as materially.

As expressed by Indian Minister of State for IT Rajeev Chandrashekar, the AIIMS incident was a deliberate attempt by a state-affiliated organized group. Such state-sponsored hackers – such as the Iranian Cyber Army – receive support from the state but may act independently. In the war in Ukraine, for example, both Russia and Ukraine have called upon cyber groups to join the battle. Cybercriminal gangs have participated at the state’s behest, further blurring the lines between state and non-state actors in cyberspace.

In the case of AIIMS, the attackers threatened to leak patient records and did not include any actual demand for ransom, displaying the complexity of attacks with varied motives. India has also been the victim of cyberattacks probing its critical infrastructure energy grid, a warning suspected to be the work of Chinese actors. The incident including the probing of the electric grid in Ladakh over a brief period from 2021 to 2022, connected to the ongoing border conflict with India.

The actions conducted by state or state-sponsored hackers have become a new normal, and the threats posed by ransomware along with other cybersecurity issues should factor in state strategies.

In view of the urgency, states are acquiring various postures to counter cyber threats ranging from diplomacy, to the use of intelligence agencies and even offensive measures. The EU has developed a cyber diplomacy toolbox that demonstrates the range of options available for different kinds of cyberattacks. This is particularly important for defining steps states can take to disrupt the networks of cybercriminal groups. The United States, meanwhile, acted against the Russia-based cyber group responsible for the 2016 elections disinformation campaign and continued actions in the 2018 midterm elections. This was conducted under the “defend forward strategy,” disrupting the attack at its source.

The coordinated effort has had an effect on ransomware groups. As observed in the Microsoft Defense Report 2022, ransomware attacks have declined due to such efforts. As demonstrated in the case of ransomware gang REvil, based in Russia, coordinated actions across different regions in the United States, Europe, and Asia led to the arrest of several suspects. However, there is a limit to the level of cooperation due to geopolitical tension.

In the case of AIIMS, linking the issue to China complicates the ransomware issue due to the tensions between the two countries. These tensions are displayed in the response, with security competition upending previous progress on cooperation against cybercrime. These changes have pushed other states to pursue more robust resilience mechanisms to counter cyberattacks.

The development of norms remains most crucial for defining the limits of cyberattacks. Here, the participation of states from the Indo-Pacific – some of the countries most affected by cyberattacks – will be crucial.

Indo-Pacific countries are still developing strategies, and several lack a clear roadmap to define the threat and actions. Yet cyber infrastructure is fragile across much of the region, with several countries only recently transitioning to IT systems due to COVID-19 pandemic. The Indo-Pacific is primarily represented by small-scale industries and fragile economies, which will impact states’ efforts to defend against and recover after cyberattacks.

Coordination across minilaterals can also serve as a guide. The Quad grouping – Australia, India, Japan, and the United States – has specifically mentioned the threat of ransomware to the region, especially to supply chains and economic development, and called for building capacity and sharing mechanisms across the region. The International Ransomware Initiative led by the United States consists of 37 states including Indo-Pacific countries such as Singapore, Australia, and India. It aims at establishing practical cooperation on mitigating criminal groups and building norms through a new U.N. cybercrime convention.

At the domestic level, measures can be adopted such as the U.S. legislation on information sharing by critical infrastructure companies within a period of 72 hours. Reports of attacks should be more public, as incident reporting is crucial for malware analysis. The public-private sector collaboration, such as Virtus Total, helps create a repository for analysis by different organizations.

For small states, however, the pooling of resources will be critical, as highlighted in the Vanuatu cyberattack. Such cooperation is emerging for the Pacific region amid the increasing cyberattacks, which require multifront coordination.