Richard Butler | Exclusive Report by Alexei Trundle of WeForum | OCT 18th, 2022

- The recent US-Pacific Islands Summit resulted in a partnership declaration, which committed more resources to the area.

- Despite rapid urbanization in the Pacific, the strategy lacked a vision for cities and urban planning.

- Governments and international partners need to invest in city governance and economic opportunities, focusing on the disadvantaged, disaster exposed, and displaced.

The Pacific Islands are increasingly the focus of competition between China and the United States. This was the backdrop to the recent US-Pacific Islands Summit, which marks a genuine shift in the political landscape of the area. All invited Pacific Island leaders – including Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, who had threatened to hold out – signed up to the US Pacific Partnership Declaration. In its Pacific Partnership Strategy, released concurrently with the Summit, the United States also committed more resources to the region.

Both documents focus on the climate crisis, the security of key resources and maritime areas, and the continuing health and economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. Each aligns directly with the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, which sets out a regional vision determined by the Pacific Island leaders themselves.

What is missing from these agreements, however, is a vision for cities and urban planning. This is a significant omission, given the rapid urbanization of the Pacific Islands. Urban planning, sub-national governance, and training need to become a core focus of international development efforts in the Pacific, as well as regional leadership. Investment in sustainable urban development is most cost effective and equitable if done in advance of rapid urban growth, rather than retrospectively.

Rapid urbanization in the Pacific Islands

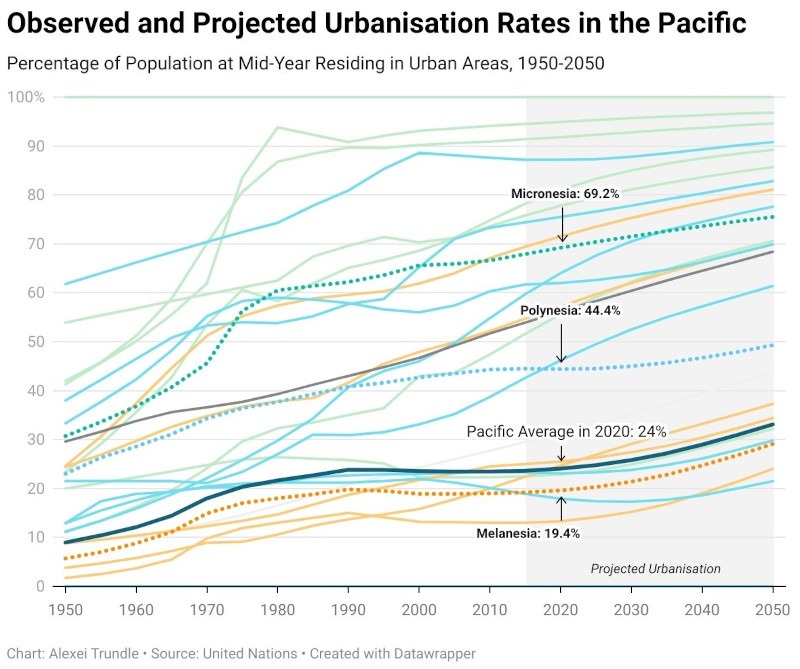

Cities and towns contribute more than half of national GDP in most Pacific Island countries. They also contain most major infrastructure, including critical health facilities. Capital cities dominate salary-based employment and opportunities for study, and facilitate international trade and travel. Nearly one-quarter of Pacific Islanders live in urban areas, a figure roughly half the global average. By 2030 this urbanisation level is projected to increase to a third of the region’s population.

New data suggests that projections have underestimated urban growth across many Pacific Island countries. This is particularly the case in the larger archipelagos of Melanesia, where a younger generation is seeking out new livelihoods and economic opportunities. Half of the Pacific’s population is less than 23 years old, and this ‘youth bulge’ is heavily geographically skewed to the region’s urban areas.

Papua New Guinea accounts for nearly half the region’s urban inhabitants, with a total population of more than 9 million. The ‘National Capital District’ around its capital Port Moresby reached a population of 760,000 urban inhabitants in 2019, which is more than 60 percent higher than the official projections that had formed the basis of planning for the capital’s development since 2008. Similar evidence can be found elsewhere in the region. Honiara, capital of Solomon Islands, is now larger than it was projected to be by 2030. Re-analysis of urban data in Vanuatu shows that one-third of the country’s population is now urban – having reached this level 10 years earlier than official projections.

As a result, policy makers are having to play catch-up, with wide-reaching consequences. Humanitarian relief efforts following recent climate-related disasters have underestimated the needs of large urban informal settlements, and urban constituencies are underrepresented politically. Overall regional measures of sustainable urban development went backwards in 2021.

The needs of the younger generation

Young, urban Pacific islanders need urban employment, housing tenure, and good governance. Pacific Island governments and their international partners should focus on supporting this, and spatial planning processes, which have been neglected or dealt with in a piecemeal manner. The region’s cities require investment in infrastructure and utilities, from roads and footpaths to open spaces and recreational facilities. Ecosystem services are especially important for the urban poor and can also be supported through creating ‘urban garden’ areas and the provision and legalisation of space for food production and sale.

Much of the Pacific’s urban population live ‘informally’, without legal tenure over the land that they occupy. Sustainable development will require the recognition and legalisation of shared spaces and services, and in some cases, relocation from high-risk sites. Many Pacific Island cities urgently need to update ageing infrastructure – particularly relating to water and sanitation – that has been poorly maintained.

Local governments, where they exist, face limited legislative jurisdiction and technical capacities. In Vanuatu, for instance, there is no technical or vocational institution that provides training on how to implement the National Building Code, meaning that it is rarely applied. A review of the Port Vila Municipal Council by the Asian Development Bank noted that the council had no technical engineering staff whatsoever. Specialist training at a regional level – with the support of higher education institutions from partner countries – may provide a cost-effective solution in the near term.

Finding a place for cities and urban areas within Oceania’s powerful regional bodies and organisations will be key to effectively tackling the Pacific’s accelerating urbanisation.